Language access: Our history and protected right

By Jodie Stanley, Municipal Language Access Network

For the first time in U.S. history, an official language has been named. Executive Order 14224 designates English as the official language of the United States—a largely symbolic move, but one with real implications.

While this order does not establish legal restrictions on other languages, it signals a shift in national rhetoric, one that could influence future policy decisions and public sentiment around multilingualism, inclusion, and access.

Language access—ensuring that translation, interpretation, and inclusive communication remain part of public services—is critical for safety, connection, and belonging.

While English is the most widely spoken language in the nation, only about half of immigrants in the U.S. (53%) speak English proficiently. With over 350 languages spoken in the U.S. today and most of the world embracing multilingualism, we must ask: What if, instead of an English-only or English-first approach, we pursued an English-plus vision—one that values language diversity as a strength rather than a barrier?

This post unpacks the history of language policies in the U.S., the impact of this executive order, and how local and state leaders can continue to protect and expand language access efforts.

Why it matters

It’s important to note that English-only and English-first sentiments are not new. While Spanish was the first European language spoken in the continental U.S.—preceded by well-established Indigenous languages—English quickly became the most common language primarily due to the prioritization of English-speaking migrants.

There are three major reasons why English has not been named the official language of the United States until this point:

- English as a majority language is not under threat. Recent census data from 2007-2019 shows that the number of people who 'speak English very well' is on the rise. An immigrant family is far, far more likely to lose their native tongue than not learn English.

- It is a denial of essential ideals of tolerance and a return to racial and ethnic discrimination that marks U.S. history.

- States should have the right to choose, and many have. North Carolina made English its official language in 1987. Hawai'i has two, English and ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi. About 30 states have taken the steps to designate English as their official language.

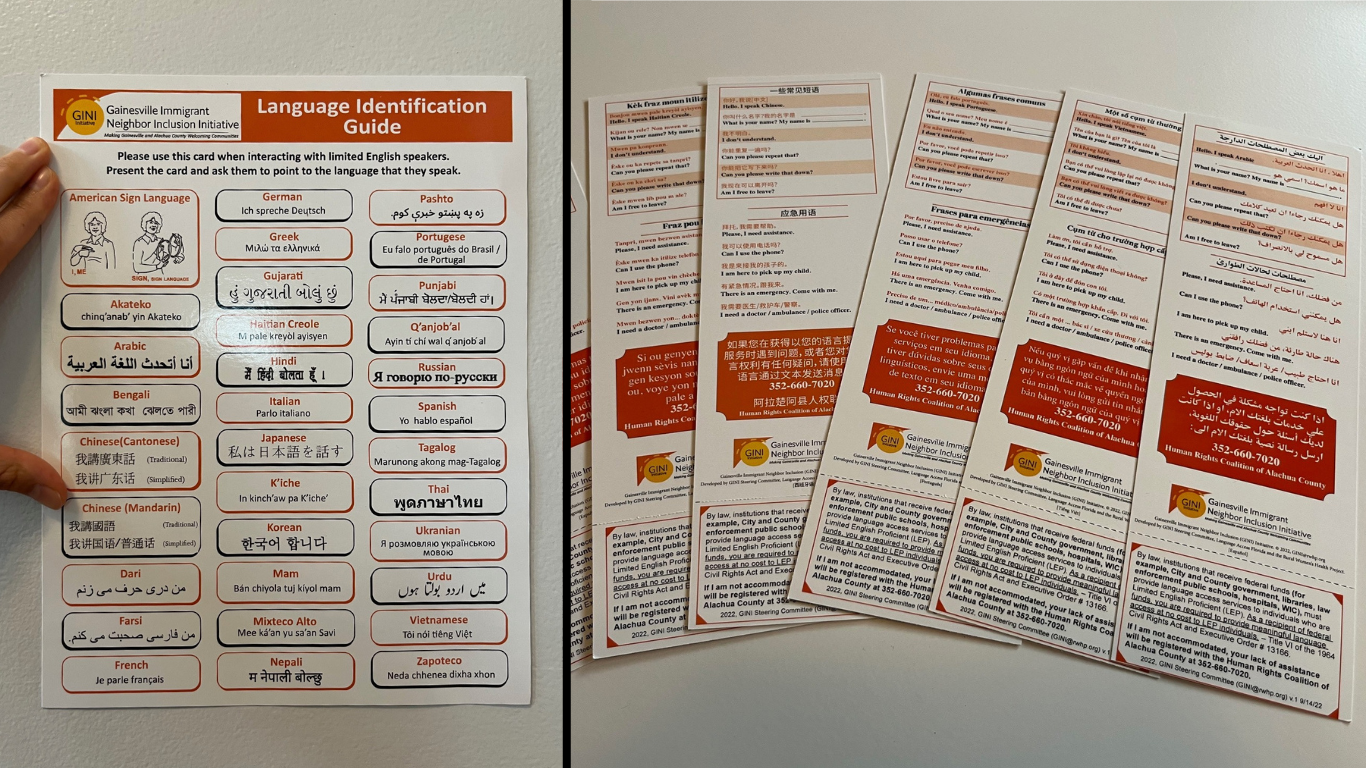

Language access can and should be prioritized and protected. Local and state leaders can continue to support and expand language access programs by understanding the history behind this new executive order and using the resources below to strengthen their efforts.

The history of U.S. official language proposals

For 250 years, many efforts were made to make English the official national language—efforts that were consistently voted down.

What we know about Executive Order 14224

Executive Order 14224 declares English as the official language of the United States. However, it does not name English as the only language.

The President’s designation of English as the official language is largely symbolic. It is a declaration, not a policy or law. To name English as the official language in a legally enforceable way would require congressional approval.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 13166, which required Federal agencies to provide language services to non-English speakers. Executive Order 13166 also laid out the framework and useful best practices for agency compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

The most recent order dismantles Executive Order 13166; this is within the President’s purview. However, federal agency leaders still have the discretion to make decisions as needed to fulfill their agency’s mission and ensure the efficient delivery of government services. The order does not mandate or instruct any agency to alter its language access services.

Executive Order 14224 does not dismantle or defund English learning programs. Advocates observe that the order promotes English learning and may be used to encourage more funding for English language learning.

The bottom line: Language access is still protected and must continue

For decades, the nation's leaders have implemented protections to prevent the mistreatment of people who speak primary languages other than English.

In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act which includes protections for national origin and speakers of languages other than English (Title VI). Even now, following Executive Order 14224, federally-funded entities are still required to provide language access as defined by Supreme Court precedent and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

Local and state leaders can and should continue to advance language access efforts. Here’s why:

- Language access facilitates global connections, business, and transportation. Locally, it boosts economic mobility, civic engagement, housing security, and health access.

- Language access and public safety are intertwined. The Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing office promotes the effective use of language access in policing.

- Speaking multiple languages protects against cognitive decline, enhancing memory and multitasking skills. It makes you more employable, opening up job prospects and earning potential.

- Communication skills improve as you learn to express yourself in multiple languages. Multilingual people develop cultural adaptability and are more comfortable trying new things and connecting with people from different backgrounds.

Language access benefits us all, as individuals, families, and communities.

Resources and calls to action

- Get started with language access in Welcoming America’s Language Access Fundamentals series. To dive deeper, join the Welcoming Network for exclusive language access training led by experts at Global Wordsmiths.

- Attending the 2025 Welcoming Interactive? Sign up for the first-ever Language Access Bootcamp hosted by Welcoming America and the Municipal Language Access Network (MLAN) when you register.

- Join the Municipal Language Access Network (MLAN) to connect with language access practitioners in government and quasi-government entities, achieve language access, and promote language justice.

- Adopt a local language access law or policy to codify language access standards, responsibilities, and governance provisions. Doing so can add stability to your language access program.

- The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held a briefing on March 21 to examine how language access impacts government services and healthcare for individuals with limited English proficiency. The recording is available and the Commission is accepting public testimony through April 21, 2025. Written materials can be submitted to [email protected].

- Read the National Immigration Law Center’s analysis: Language Access and Civil Rights: Analyzing the Impact of the Executive Order Claiming to Make English the Official National Language

- Read Migration Policy Institute’s analyses:

- The Asian Law Caucus, California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc., and Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles have developed an FAQ to help community groups and state and local officials understand the reach and impact of Executive Order 14224.